Water Deities and the Embodiments of Multiplicity

Yemọja is a Yoruba deity who presides over water bodies. She is said to be powerful, protective and maternal. There are other Afro-diasporic water spirits who are either different manifestations of Yemọja, are syncretic versions of her, or are imagined to function in a similar way. For example, one might think of Mami Wata, La Sirene, lwa Ayida Wedo or even Our Lady of Regla who’s North-African Spanish Catholic derivation is connected to the sea. As a result, Yemọja has been repositioned, revived, upheld over time. She represents and belongs to a myriad cultures who are today interconnected because of various type of maritime voyages that took place over several centuries.

Perhaps this is why Scherezade García’s figures are at first glance reminiscent of a type of Yemọja. Many writers have personified the sea or likened it to historical repository. Therefore, if water can hold history, then García’s beings carry the keys to humanity’s archives. Often situated in water, her figures represent narratives of hybridity that have persisted over time, as a result of, and in spite of, Columbus-era explorations, slavery, colonial exploits, political precariousness and more recently, the perilous pursuit of economic opportunity. They embody a form of creolization informed by cultures, religions, cosmologies and histories from every continent, but mainly by people groups who have moved across the Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean and Mediterranean seas. In a 2016 body of work titled Super Tropics García makes direct reference to Yemọja yet consider her exiled.

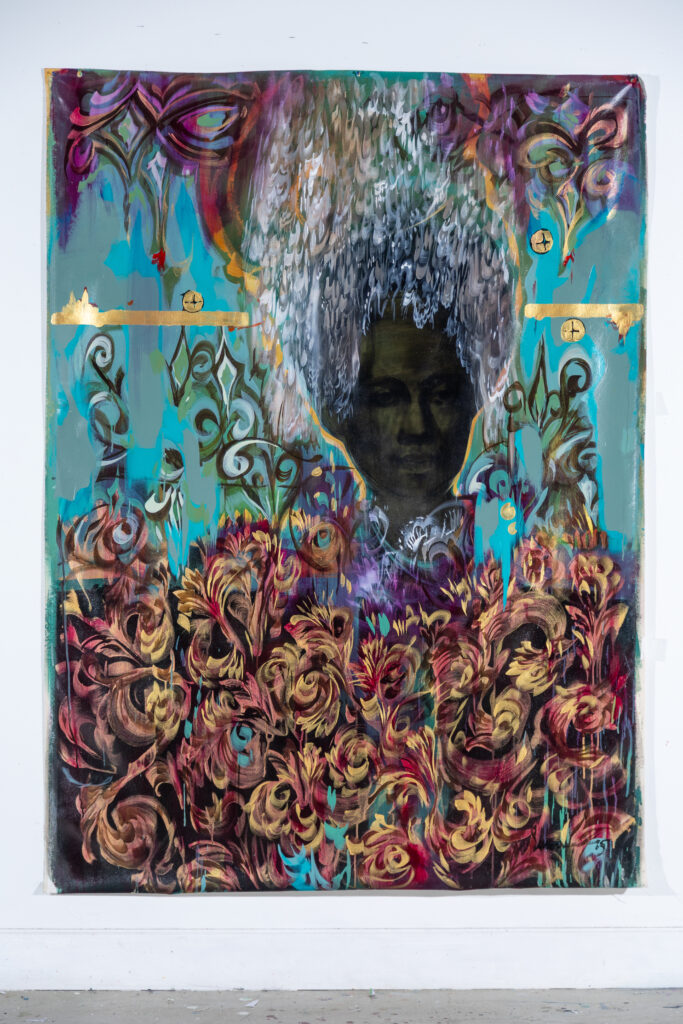

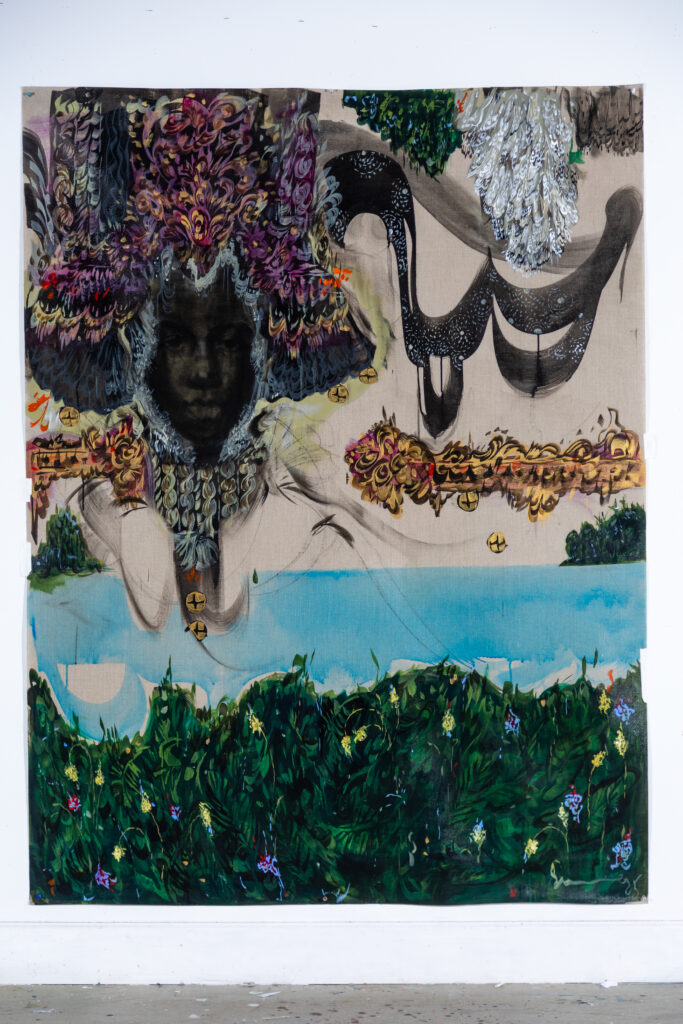

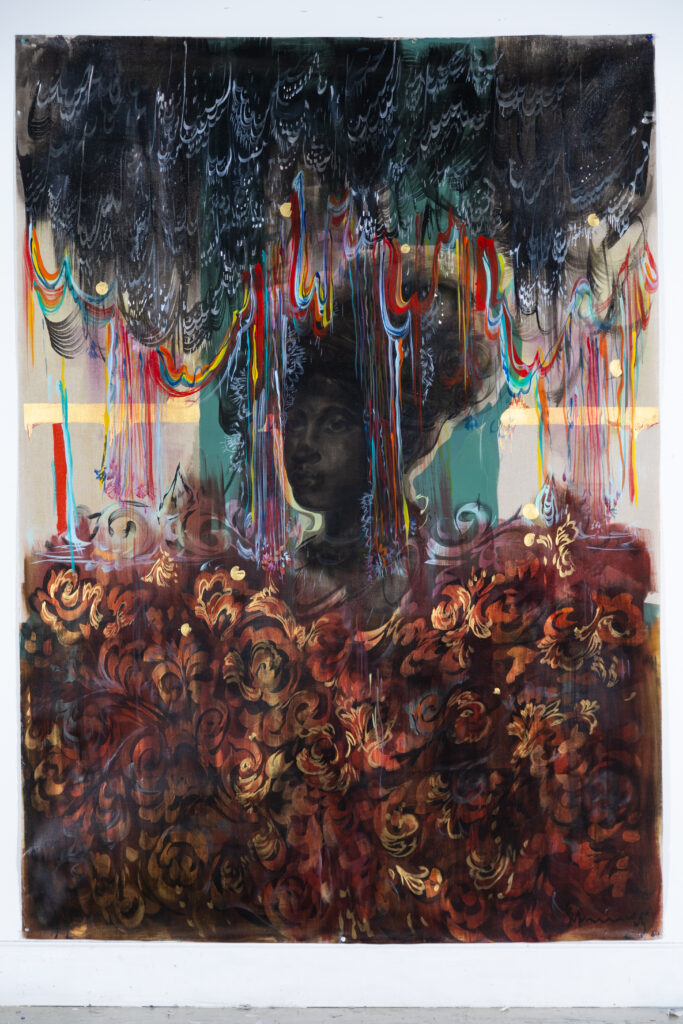

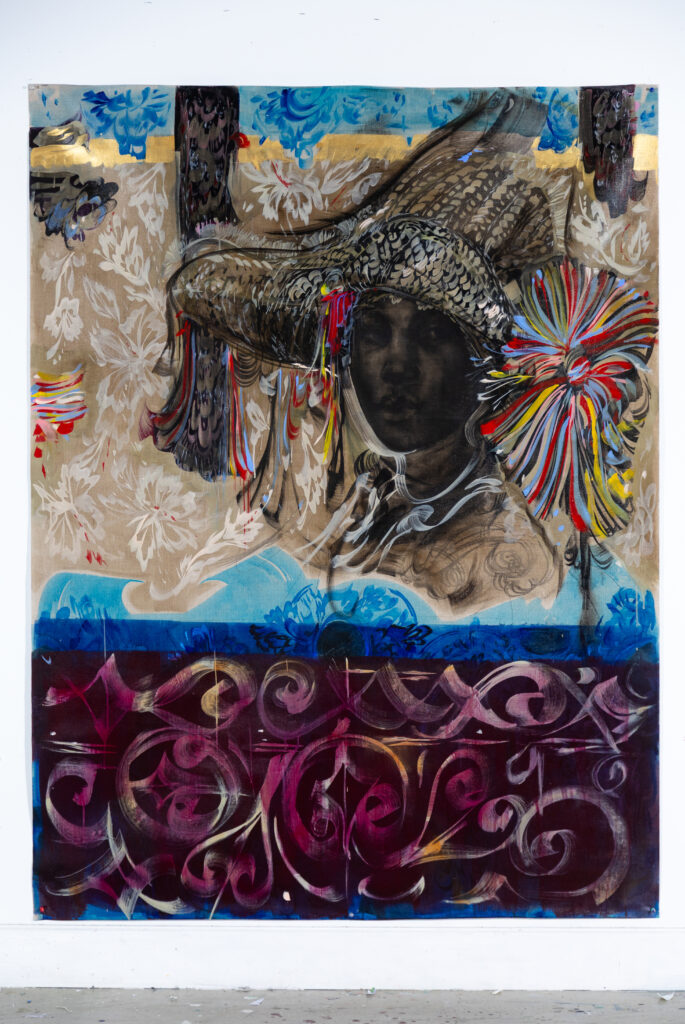

It may be the translucent, dark, cinnamon- golden skin tones that make García’s beings other worldly. Their soft monochromatic hues usually contrast the vivid, gestural marks that adorn and surround them. Their extravagant regalia which consists of elaborate gold jewelry, and intricate ruffs gives them a weighty stature. There is often a contradiction between the calmness of these god-like beings, and the movement of the water, lace and flora. No matter how turbulent the sea that they are situated in appears, they traverse it with gentle composure. The inclusion of rosary beads and saintly postures enhances their celestial aura. Their faces gaze back at us, at each other and at the distant lands. Always in repose, they have presence and are present. They are seers, they embody the past, and have the ability to understand the present and to see far into the future.

Yet, as is typical in García’s practice, everything is intentionally fluid and can carry multiple meanings. The beings in her work could be angels reincarnated from older bodies of work. García recalls listening to Roberta Flack Angelitos Negros, released in 1969, as a child, and even in her youth she wondered why depictions of Black religious iconography was so scarce at the time. In response to this, and the complicated history of imperialism, García tends to insert, ‘Catholic iconography with mixed-race warriors and angel’s [as] a way to colonize the colonizer by appropriating, transforming, and creating new icons.’

Still, these Yemọja-esque, saintly angels, are also ancestors and family members. They are what García calls ‘collective portraits. 2 This is because the figures are based on photographs of great aunts, daughters, nieces and other women connected to her. They represent the multiple generations, nationalities and ethnicities within García’s lineage. Her portraits are like portals that reveal layered personal and collective histories. However, they are also mirrors that insist on both self and societal reflection.

García’s work is full of tension and contradiction. For example, the floats and plastic sharks denote danger, yet can also connote leisure. She draws our attention to those risking their lives on torrid seas in search of greener pastures, while critiquing paradise narratives. Similarly, brightly colored floats, regal curly or braided hair, excessive lace, feathers, ribbon, hats, tropical flora and waves, in contrast to the soft faces, have been used to frame the figures in her compositions in order to make them the focal point. However, in works such as the Apuntes de Las Americas she has framed them more literally, through the insertion of thick overbearing, collaged, ornate gold gilding. These lavish frames, with wild flora protrusions, echo the extravagance of baroque style which have always informed García’s practice. The framing may be a metaphorical painterly attempt to canonize the figures, who in turn represent numerous complex stories.

Everything in García’s work has movement for the sea is never completely still, and people’s stories keep evolving. Movement is achieved through repeated strokes, recurring

printmaking, collage, and re-layering in each artwork. At times, the waves and patterns resemble script, perhaps a play on Charles Dicken’s 1842 ‘Notes from the Americas,’ as well as contemporary discourse emanating from the Americas, particularly around documented and undocumented persons.

At a time when the immigration issues in North America have intensified an already heightened political climate, García’s work reminds us of the complexity and beauty of our humanity. Aptly titled, Sea of Belonging: Golden Skin this body of work continues her tradition of bringing together ideas around identity, multiple- heritage and plurality. This timely work gently challenges singular dominant homogenous narratives that are founded in exclusion. Just as the narrative of Yemọja has persisted in many cultures for centuries, García’s work is a testament to human survival. Through subversion, people will endure and maybe even find beauty in the chaos.

Tandazani Dhlakama

August, 2025